As the Global Pound Conference Series 2016-17 draws to a close, it is time to take stock and consider how both the data analysis and conversations from each event might inform the future of Dispute Resolution.

As an academic, I am wary to avoid drawing conclusions before the final analysis is complete; but as contributor to the series from design to data analysis , I would like to share some of the themes I see emerging from this ambitious project.

Emerging themes:

- The move from ADR to DR

- Consideration of the sophistication of parties may prove crucial

- Education is key

- Lawyers see things differently from other stakeholders, including parties.

1. The move from ADR to DR

When we started the project, there was contention among committee members about the definition of different dispute resolution processes. In particular, the definition of ‘ADR’. Is it alternative DR, appropriate DR..?

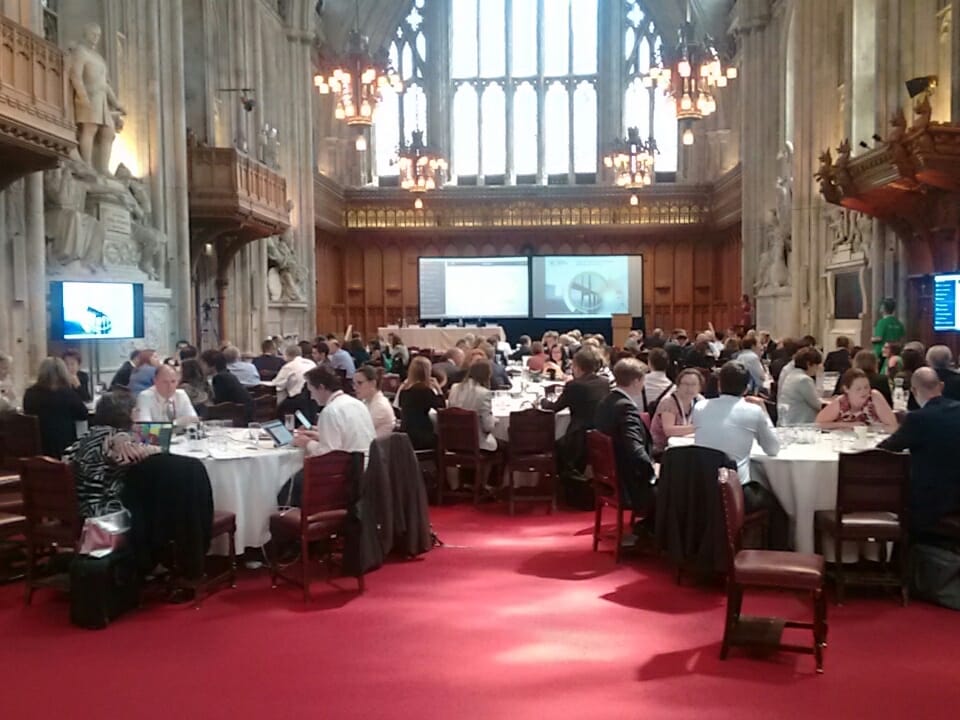

Facilitating the London Pilot, February 2016

As the project gained momentum, conversations moved from the idea of there being two distinct poles of DR. At one end, the adjudicative processes (such as litigation and arbitration) where the process and outcome are determined for the parties, and at the other end, the non-adjudicative processes (such as mediation), where parties have the opportunity to be decision-makers.

From these conversations, two things became clear. First, many stakeholders were starting to see the benefits of hybrid processes such as med-arb. Secondly, there was a realisation that dispute-savvy parties desire tailored processes that require DR practitioners to be familiar with a range of skills across the DR process continuum.

As such, we are now in a world where we no longer have a strict delineation between adversarial processes and non-adversarial processes. Now, all processes can co-habit within the DR landscape.

2. Consideration of the sophistication of parties may prove crucial

The GPC Series invited participants to pay attention to the parties’ perceptions. As a result, we now have evidence (see pp 48-50) that parties who are unfamiliar with DR processes have different wants, needs and expectations from dispute-savvy clients.

Facilitating the collection of the data at the inaugural conference GPC Singapore, March 2016

The GPC has revealed that the ‘experienced user’ and the ‘sophisticated user’ may not always be the same. Parties who are familiar with a single DR process may not be dispute-savvy, as they will view a dispute through a limited lens. A dispute-savvy client will be able to look at each dispute individually, and may anticipate a tailored solution that draws on a variety of DR skill-sets.

As a consequence, if practitioners want to satisfy the wants, needs and expectations of their clients, they must consider the sophistication of the parties participating in DR processes.

3. Education is key

This is not a new concept in the DR space. What has been made clear from the conversation is the importance of reviewing and reframing our educational focus.

This means education to facilitate change, rather than our current focus of building a heightened awareness about DR. Without careful thought, DR professionals and academics may miss the opportunity to keep pace with the rapidly changing business world, which routinely incorporates pre-escalation and/or de-escalation systems into business models and dispute clauses into contracts.

Practical and skills-based training and education for both the legal and business communities will be the way of the future for those who do not wish to be left behind.

4. Lawyers see things differently from other stakeholders, including parties.

Unsurprisingly, the cumulative results of the GPC quantitative data supports the idea that lawyers play an important role in DR. It is both a strength and a weakness. At many events lawyers were seen as having the most influence in bringing about change, but they were also seen as the most resistant to it.

As our colleague Dr Olivia Rundle has identified, there is ‘a spectrum of contributions that lawyers can make‘ in DR. Combine this with the idea that clients at different levels of sophistication want different things from their lawyers (see pp 66-69), and it becomes abundantly clear that, to move with the times, some lawyers may need to adopt a more flexible mindset, with room for both adversarial and non-adversarial strategies.

Lawyers who understand these challenges and adapt to them have the opportunity to play an integral role in the future of DR. Without this, they will be left behind.

When considering the themes discussed in this blogpost, it is important to remember that the GPC Series 2016-17 collected data in relation to commercial dispute resolution. That said, there is feasibility for the insights gained from the project to prove fungible to other areas of DR. For example, family or community disputes.

I invite other academics to use the GPC to inform further research as we move from a series of Global Pound Conferences to a Global Pound Community.

Written by Emma-May Litchfield.

This article was first published on the Australian Dispute Resolution Research Network, for the original please click here.

Emma-May Litchfield is an academic in Australia, who focuses on empirically-based applied research. She works at both the Melbourne Graduate School of Education at the University of Melbourne and the Graduate School of Business and Law at RMIT University. Emma-May also sits on the Executive and Academic Committees of the Global Pound Conference Series 2016-17.

Together with Danielle Hutchinson, Emma-May co-founded and directs the consulting firm Resolution Resources, who provide dispute resolution services and solutions both nationally and internationally. Together they work as dispute resolution advisors, providers and educators.

Pingback: Ask An Expert: Rosemary Howell – Global Pound Conference Blog